It's All Gonna Break: Revisiting Indie Rock's Canadian Invasion

In the latest SUCH GREAT HEIGHTS B-side, veteran Toronto journalist Stuart Berman takes me back to that early 2000s moment when seemingly every cool new indie rock band was from Canada

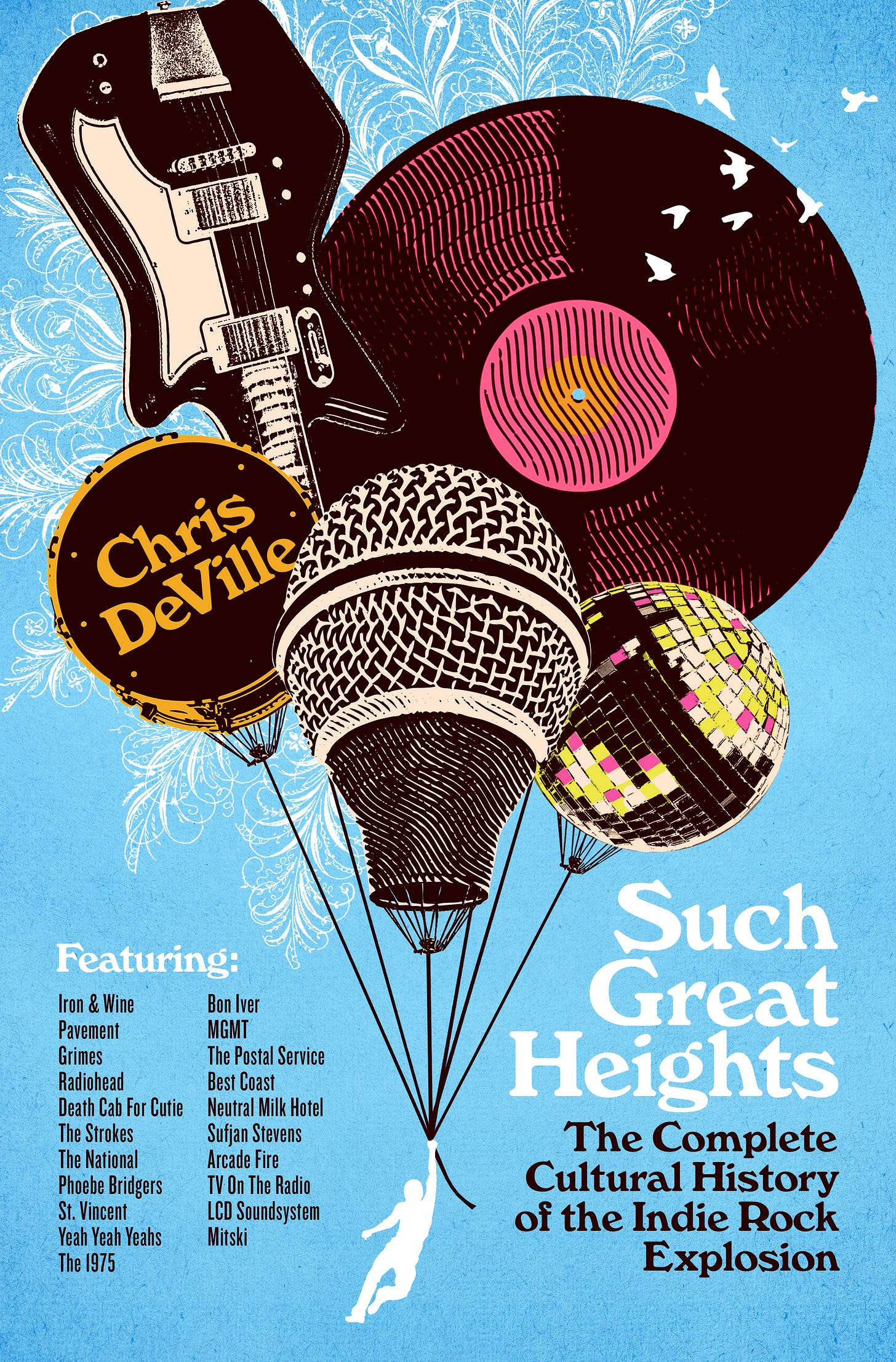

My debut book SUCH GREAT HEIGHTS: The Complete Cultural History of the Indie Rock Explosion is about how indie rock impacted the mainstream and the mainstream impacted indie rock in the 21st century. It’s out Aug. 26 on St. Martin’s Press, and you can pre-order it right now. (I explained the concept in-depth here, and there’s a very positive Publishers Weekly review here.) At this Substack, I’ve been rolling out bonus material, including “B-sides” about key storylines from indie rock’s glow-up that are only covered glancingly in the book.

One of those subplots that is implied but not directly addressed on the page is the explosion of cool new Canadian indie bands in the early 2000s. The New Pornographers (and associated acts like Neko Case and Destroyer), Broken Social Scene (and associated acts like Metric, Feist, Stars, and Do Make Say Think), Godspeed You! Black Emperor, the Constantines, the Unicorns, Arcade Fire, Wolf Parade, Death From Above 1979—the list goes on and on. So much exciting alternative rock was impacting the US from north of the border in those days, including several acts that seemed to be charting the course of indie music in real time.

The 2000s Canadian indie rock zeitgeist has been explored in-depth by figures like Michael Barclay, author of Hearts on Fire: Six Years that Changed Canadian Music 2000–2005, and my guest today, Stuart Berman. Berman is the author of multiple books about Canadian music including the Broken Social Scene biography This Book Is Broken. For decades, he’s been covering music in and around Toronto, where he used to write for the newspaper Eye Weekly and currently works as a producer for the CBC radio show Commotion. He continues to publish great writing everywhere from Pitchfork to here at Substack, and I’ve commissioned him to write amazing pieces like this one for Stereogum, where I’m the managing editor.

A few weeks ago—after the word “tariffs” became inescapable but before Mark Carney was elected prime minister—I got on a video chat with Berman and asked him to walk me down memory lane. In anecdote-packed bursts, he flashed back to iconic early moments from some of the aforementioned bands while also discussing the crucial roles played by less heralded greats like the Hidden Cameras and the Dears and indie-rock-adjacent figures like Peaches. His perspective was compelling, so I mostly just got out of the way and let him cook. Our conversation is below, edited for concision and clarity.

What was happening in the late ’90s leading up to the big Canadian indie music boom of the early 2000s? Was there a boom before, but people just weren’t paying attention?

What I always say is people forget how closed off Canada was from the international music conversation pre-2000, 2001. It's almost as if there was a tariff blockade or something, preventing us from accessing the American market. I mean, when you go back to the ’90s, you had some isolated cases of Canadian artists signing with American labels, like Sloan signing DGC. Sub Pop scooped up a few Maritime bands like Jale and Hardship Post. But the reality is, Canada had its own post-Nirvana effect where the major labels in Canada—Sony Music Canada and EMI Music Canada and Warner Music Canada—were scooping up a lot of alternative rock bands and or, you know, kind of fake alternative bands with pretty boy lead singers. So there was definitely a lot of excitement over alternative rock culture within Canada.

But again, very few of those bands connected with international audiences. Because Canadian major labels, for the most part, exist to create Canadian success stories—you know, very focused on breaking bands within Canada. And there's no guarantee that if you're signed to Warner Music Canada, that Warner in the US is going to want to pick you up for US distribution.

So you had a lot of bands just kind of playing in this closed system. And then Canada itself is like a tough market to tour. The big cities are like 10 hours apart. So bands were kind of locked into this kind of unforgiving system. They got a lot of MuchMusic airplay. I'm talking about the sort of bigger Canadian alt bands like Our Lady Peace, who actually did—

Yeah, they permeated the US market.

But on the sort of more indie-leaning level, your Thrush Hermits or your Super Friendz who were sort of like the bigger bands out of Halifax. It was kind of a tough existence to have to tour these long distances and then not also be able to get any American media attention. Because if you flip through like a Spin magazine or a Ray Gun magazine or Option or whatever, or even Rolling Stone, you didn't find a lot of Canadian bands being covered.

If you look back at the early Lollapalooza lineups from the ’90s, which you would kind of hold up as, like, “This is what's happening in alternative and indie culture right now,” you didn't see any Canadian bands there. And for a lot of people, Canadian music was kind of a joke. Because the stuff that did export well tended to be super big pop stuff like Celine Dion or Brian Adams or Shania Twain. We were doing really well on the massive pop level. But in terms of alternative-specific bands, there just wasn't a lot of crossover. These bands weren’t being written about in the Village Voice or any of the big taste-making media publications at the time. Or the NME over in England as well.

Being specifically in Toronto, we have a huge British Anglophile influence here traditionally. There's a lot of UK expats who live in Canada. So British bands always tended to do very well in Toronto before they blew up elsewhere. But then then you also have the American influence as well. So we were kind of like in this tug of war between our parents overseas and our big brother to the south. So it just didn't give a lot of room for Canadian music to have a lot of oxygen beyond sort of like specific niches.

So is this strictly an internet thing where the internet allowed more attention to come to the Canadian scene, or was there also an uncommonly fruitful creative period happening?

It's a little both. I think, in the ’90s you had this cycle of alternative boom-bust. In the early ’90s, a lot of alternative bands were getting signed, getting on MuchMusic. We had this alternative show called The Wedge, which is kind of like our 120 Minutes. So they put a lot of cool indie stuff on there in this half-hour every day. And it was on after school. So that was a good way for an indie band to get attention. But then it [in the] late ’90s kind of fell apart. Major labels started signing electronic bands or pop artists, you know, just kind of like entering the Britney and Backstreet Boys era. And then nu metal, all that, you know, drowning out whatever indie rock bands had a fighting chance in the early ’90s, kind of it all got quashed.

So yeah, it did feel symbolically like 2000 was this sort of rebirth, regeneration moment. And in Toronto specifically, you had a new, slightly younger generation coming up, and people from the suburbs or satellite cities moving to Toronto and bringing new ideas. One big one was the Hidden Cameras, who are from Mississauga, which is kind of like, I guess you could call it the Newark to [Toronto’s] Manhattan. You know, it's the city right next door to Toronto. Like there's very little actual geographic separation. But it is kind of a more suburban environment.

So Joel Gibb, the lead singer, he started out four-tracking on his own. And then he just built up this crew of people and turned these shows into these circus-type environments with dancers and overhead projections and just this like really kind of celebratory energy. This is also coming out of the post-rock era in the late ’90s where everyone kind of retreated and started making that insular instrumental music.

And that certainly is happening in Canada at that time.

Yeah, I mean, another huge catalyst was Godspeed. Again, there were Canadian success stories like Sloan earlier, and then Godspeed. But they all seem like isolated incidents. Like it seemed like there wasn’t this connectivity of a Canadian music identity. But yeah, Godspeed was a huge one in the late ’90s because like the British press picked up on them and tried to turn them into cover stars, even though they refused to have their face on the cover. So they just ran a manifesto.

That was a huge moment in terms of showing left-of-center music. I guess the other big point about like the early ’90s is that a lot of what was coming out of this country, you could say, was like the Canadian version of a popular American sound. So you had a lot of grungy rock bands trying to do the Nirvana thing. I mean, even early Sloan was kind of in that mold, before they developed their own sort of power-pop language. So Godspeed, I think, was the first instance of something you could point to where it's like, “OK, this is not riding on any kind of trend. This is its own thing.” And they had this mystique about them.

And I don't even think about them as the only example. Like, there was Do Make Say Think…

Yeah, that was all happening at the same time, too. There's layers of any sort of music scene narrative. There's layers of activity. And obviously there's the stuff that gets the most mainstream attention. But then, below the surface, there's people doing all sorts of weird shit. Like the indie DIY scene in Toronto in the ’90s was very thriving, very active. It's just nobody had any aspirations of even touring outside the province, really. It was all very insular. So yeah, Do Make Say Think came out of that moment. They were sort of running in parallel to Godspeed in many ways. And they were kind of like our Toronto version of that. But yeah, Godspeed just got that massive spike in international interest, and then they got the Kranky Records reissue, which put them in front of a lot more people. But again, that just seemed like that was just something happening to Godspeed, not necessarily Montreal or the country as a whole.

In Toronto here, you had the Hidden Cameras kind of bringing this new energy, especially like a queer energy, which is not something that was that pervasive in indie rock circles. The other cool thing about the Hidden Cameras is they combined really classically trained musicians like Owen Pallett and then like complete amateurs who've never played an instrument before. It's like a collision of artful craftsmanship and complete anarchy at the same time. I think Arcade Fire would be the first to admit they took a lot of their aesthetic cues from the Hidden Cameras.

I feel like the Hidden Cameras have kind of been a bit lost to history, sadly. But in Toronto, like circa 2001, they were on the front lines of this new kind of movement happening. And they were sort of affiliated—not directly, but just through common membership—with Three Gut Records, which was a label that started in Guelph, which was a college town about an hour outside Toronto. And they brought the Constantines a wider audience in Toronto, and the Constantines eventually moved from Guelph to Toronto as well.

So Hidden Cameras were popping off, and then Broken Social Scene [were] kind of transitioning out from an ambient basement project very much in the sort of Do Make Say Think world. I don't think it's any coincidence that over the course of 2001, they turned it into this multi-headed live band ensemble. Because that was the energy that bands like Hidden Cameras were bringing. And so I think Broken Social Scene really wanted to be part of this moment, this really exciting moment. Because when you listen to the early Broken Social Scene stuff, it's total basement zone-out music. And then all of a sudden, their next record, it's this multi-headed rock orchestra.

We also had, in Toronto, a really strong system of alt-weeklies—like I worked at one called Eye Weekly, there was another one called NOW Magazine—who were covering this stuff very closely on a weekly basis. And even at the daily [level], we have four daily newspapers here, and they all had a dedicated music critic who could also have some freedom to cover left-of-center stuff. So you had a good base of media support. And again, the internet was just starting to become a source for new reliable information on what was coming.

And then I also say another catalyst for the moment was the now unfortunately named New Pornographers. So they dropped Mass Romantic in the fall of 2000. And that was a record that got the press attention south of the border and in the UK. They went down to South by Southwest. The first time I ever went to South by Southwest was March of 2001. They played a big showcase at La Zona Rosa, and Ray Davies came out and sang “Starstruck” with them. And that got them a huge bunch of attention.

They were out in Vancouver. So it didn't necessarily feel like a movement of anything at that point. But again, being in Toronto, not having a lot of of our bands get that sort of US attention, it felt like, “Yeah, we're going to adopt the New Pornographers as our team.” It's kind of like when there's a Stanley Cup and there's only one Canadian team left. Like, “OK, I'm a Winnipeg fan now.” It was so rare for bands to get written up in, you know, Q Magazine or Uncut overseas.

The Russian Futurists, they were like this one-man synth pop band, kind of like a proto-Postal Service type thing. And I remember they started getting some US attention in the early 2000s for their first record. And again, that seemed like, “Oh my God, they got written about in Q Magazine. This is insane.” That's how deprived we were for validation. That's sort of a common thing about the Canadian sensibilities. We're always craving attention from outside our borders. Or bands don't get popular here until they get popular overseas or in the States.

But that started to change in the early 2000s where it's like, “Oh, no, we have some great stuff here that we want to celebrate. And it's just as good and innovative as what's happening anywhere else.” Because this was also a time when the Strokes thing was blowing up. And that was funny—there was definitely a huge appetite for that here. But it didn't feel like any of the Canadian bands had a common sound, per se. It was more like a common aesthetic. It was sort of an inclusive crowd-participation type welcoming vibe to them. So even though the Constantines were a much harder-edged post-hardcore-influenced band, they brought this celebratory sort of soul music quality to their performances.

So the same people going to Hidden Camera shows were also going to Constantines shows, and were also going to Broken Social Scene shows. Royal City was another band that were doing well locally. They were also on Three Gut. They were much more kind of like a Will Oldham, Palace Brothers [thing]. Feist was in the band very briefly around 2000. And so when Geoff Travis came over to sign the Hidden Cameras to Rough Trade, he also scooped up Royal City at the same time. I interviewed Geoff Travis at the time. It was like Jac Holzman going to sign the MC5. Unfortunately, Royal City sort of petered out by mid-decade.

There was a lot of creativity happening in terms of where shows were being held. A lot of these groups would bypass the traditional bar circuit. Like, the Hidden Cameras, especially, would host shows in churches, old porno theater houses, art galleries, things like that. So it created this idea that you're not just making music to help bar sales. You're trying to create more of a moment.

How much overlap was there between Toronto and Montreal? Were they feeding off of each other?

Definitely, especially since some of the Arcade Fire guys actually went to school in Guelph. So they were kind of friendly with that whole Three Gut scene early on. The first time I actually became aware of Arcade Fire was going to see Jim Guthrie, who is a DIY artist who was a member of Royal City. But he also did his own solo thing, and he was doing a CD release show at the El Mocambo. And I remember showing up just in time for the headliner, and a friend of mine there, Michael Barclay, the writer, was just like, “You just missed the best band in Canada.” Which was Arcade Fire. And so then I caught them a few months later opening for the Constantines. I remember they opened with “Wake Up.” It was like standing in front of a jet turbine. It was pretty amazing.

And then we also had this message board called Stillepost, which was a place where bands would post upcoming shows. When you logged on, there were different city boards, Toronto, Montreal, what have you. There was a lot of cross-posting, cross-promotions there. So yeah, like, the Unicorns would come here all the time. Arcade Fire early on when they were still playing small rooms. And then the Pop Montreal Festival also started, I believe, in 2002. There were definitely a lot of Toronto bands going there.

Another huge band for me personally, and I think for this moment, were the Dears. Who came to me as sort of like this post-Britpop type of band. But then I would see them live. And to this day, hands down, one of the best live shows I've ever seen is the Dears circa 2000, 2002. They were just ferocious. And the records were so ornate and stately and very proper. But live, they were just in beast mode and just would attack songs. So they played Toronto a ton and built up a huge following here pretty fast. And in a way, you know the way these things work, they got leapfrogged. Arcade Fire kind of leapfrogged them in international attention. But again, I would say if you were to talk to Arcade Fire, they were probably taking notes from the Dears early on.

But I mean, that's not taking anything away from the early Arcade Fire. They were the kind of band that you saw live early on and were like, “Holy shit.” And I think what gets lost in the conversation with them is they were kind of like a violent band. There was so much emotion pouring off the stage. Like, you were afraid someone was actually going to get hurt.

Yeah, I saw them in 2004. So there was another year of refinement, I guess, but they were definitely still playing drums on each other's helmets and whatnot.

They were kind of a volatile entity at first. I feel like there was at least one incident where they were supposed to play a Toronto show. And they're like, “No, we broke up.” So there was a lot of this kind of unstable quality to them early on. But that, I think, made those early shows exciting as well. Because it did feel like it could all fall apart.

So I feel like that's when the sort of Toronto-Montreal connection started happening. It felt like, “OK, there is a ton of stuff.” And then, on a more commercial level, Sam Roberts was blowing up here. And then everything that came with the Broken Social Scene package—Stars, Metric, Do Make Say Think got sort of a bump in visibility from that as well. So, yeah, it felt like it was a very crowded field all of a sudden. And then you have, the Broken Social Scene Pitchfork review is kind of like, you have a spike.

Yeah, I was wondering if Pitchfork was the catalyst.

I mean, yeah. Broken were already sort of setting up their US strategy before that review dropped. I think they already had a distro deal with Caroline and a US tour booked and South By dates set up. But that just put the album in front of so many people's faces so much faster.

It was just perfectly timed for that moment, both in Pitchfork's history and where the internet was at. Because You Forgot It In People, there was a local release in October 2002. And then I think the US release was spring ’03 through Caroline. But the Pitchfork review was, like, February. So the album hadn't officially been released in the US yet. But because it was out in Canada, files could be shared.

And where Pitchfork was at at that time was, they were starting to develop this reputation as a tastemaker. And so when they give this obscure Canadian band a 9.2—which is a score they normally reserve for, like, Wilco and Radiohead—that created a lot of instant intrigue: “Who the hell, what the hell is this?” So yeah, by ’03, it was like full steam ahead. And then we have, like, Wolf Parade and things. And you had the New York Times coming out to, like, do the Montreal scene report. And Funeral was fall of ’04.

You mentioned Three Gut Records. Speaking of important Canadian indie labels at the time, I know there was some talk of Funeral coming out on Alien8 before they ultimately went with Merge. I remember reading that in the Merge history book.

I think Arts & Crafts were also snooping around Arcade Fire. They were that band that everyone wanted a piece of at that point. Because every time they came to Toronto, they were playing bigger rooms. I saw them play a club called Sneaky Dee's, which was, like, an upstairs 200-cap room. And then, a few months later, they were playing Lee's Palace, which is a 600-cap room. And then they were playing the Danforth Music Hall for three nights, which was, like, 1,200-cap. That's, like, all over the course of, like, 18 months.

I remember in the summer of ’04, there was a music festival on Toronto Island. Toronto has a little network of islands that are just, like, a 10-minute ferry ride. So they used to do annual music festivals on the island. I think in ’04, it was Sloan headlined, but on that bill, you had, like, Broken Social Scene, Sam Roberts, Constantines. And then the first two bands, at like 12 p.m. and 12.30 p.m., were Death From Above 1979, and Arcade Fire. It was right before Funeral, right before You're A Woman, I’m A Machine came out. So they were the early bird arrival bands. Going to that festival, I remember feeling, “OK, this is a moment.” You know, there's 10,000 people here. And they were playing small clubs a year ago. That's wild.

You mentioning Death From Above reminds me: How important to this phenomenon was the fact that Vice originated from Canada?

Definitely once things started popping off, like mid-decade, every afterparty seemed to be a Vice party. DFA were, like, in their own world because they came out of more of, like, the post-hardcore scene. They also lived in the East End of the city, which was kind of, like, most of the musical activity in Toronto happened in the West End. And so that was sort of like this geographic and ideological divide. So they were real outsiders. But they were kind of becoming a bigger name in the post-hardcore scene. So they kind of already had their own thing going on. But they ended up signing to Last Gang in Canada, which was Metric's label. So they kind of got ushered into the greater Canadian conversation with that.

And to be honest, I was kind of shocked at how big they became. Because early on, they were a very abrasive band and very different from what the Hidden Cameras were doing or what Broken Social Scene were doing. Both in the sort of minimal two-piece setup and just the sound was obviously much heavier. But they had just enough of that danceable element to kind of ride the dance-punk wave that was also happening at the time. So I feel like they kind of rode more that wave to success than the Canadian narrative. But they kind of got absorbed into [the Canadian story]. Metric were another example who make music that's actually very different than Broken Social Scene and kind of could tap into that post-Strokes moment. They became one of the bigger bands to come out of this Canadian moment.

Before we go, I know you also wanted to mention Peaches as an important forebear for this explosion of Canadian indie artists. I remember seeing her open for Queens Of The Stone Age in 2002 and not really getting it, and then a few years later a huge segment of music under the “indie” umbrella sounded like that.

The reason I thought about Peaches is because electroclash was, like, secretly the most influential movement in the last 20 years. In the sense of not just bringing dance music as culture into indie aesthetics, but also broadening the audience, more women, more queer artists. And I think that naturally lends itself to like more of a poptimist sort of direction than you get from angry white dudes playing post-hardcore music. So, yeah, I feel like we're still living in a post-electroclash world.

SUCH GREAT HEIGHTS: The Complete Cultural History of the Indie Rock Explosion is out Aug. 26 via St. Martin’s Press. Pre-order it here.